Ready to see the market clearly?

Sign up now and make smarter trades today

Trading Basics

January 18, 2024

SHARE

Crash Course On Risk Management In Trading

Intro

When it comes to financial markets, it is virtually impossible to avoid risks completely. The best thing a trader or investor can do is to mitigate or control these risks.

Most traders are already familiar with many aspects of dealing with risks and understand why it’s important. Here, we cover the less known nuances of risk management in trading, demonstrating various sources of losses.

We have decided to present the article in the form of Questions and Answers to make it relevant and easy to read.

Q/A

Q: What is a risk in regards to trading?

It is the risk of losing your money up to closing your trading account completely. Reducing the losses is at least equally valuable as increasing the gains.

Q: How does risk management work?

Typically, the risk management process involves five steps: setting objectives, identifying risks, risk assessment, defining responses, and monitoring. Depending on the context, however, these steps may change significantly.

Q: What causes of losses are there?

There are several reasons why a strategy or a trade setup may be unsuccessful. For example, a trader can lose money because the market moves against their futures contract position or because they get emotional and end up selling out of panic.

Emotional reactions especially cause traders to ignore or give up their initial strategy. This is particularly noticeable during bear markets and periods of capitulation.

But these are the most common ones:

- Cost of trading

- Bad luck

- Lack of competitive advantage

- Obscure / unexpected / not considered sources of losses.

SEE MORE DETAILED ANSWERS BELOW ↓

Q: My commission’s rate is low. I win or lose each trade by a chance of 50%. Why would I lose in the long-term?

Suppose you pay 0.1% commission rate and you have a 50% chance of guessing the price direction correctly. After trading 200 times, you lose ~20% of your fund on commissions only. Depending on your trading style, you may also add part of Bid/Ask spread to the cost of trading.

Q: Is there anything to do with bad luck?

In such a complex environment as trading, there are always random factors that we treat as noise. We have to accept a certain amount of “bad luck” (as well as “good luck”) due to these factors.

However, we should not confuse them with the lack of competitive advantage. Many of those random factors are not random at all. We just treat them as random when we don’t have enough relevant data about the origins of that “noise.” We also may not have enough computational or visualization power to interpret this data correctly.

Q: How to improve my competitive advantage?

In short, by unveiling, as much as possible of the said “randomness” and making it your competitive advantage.

- Trade in industries where you have a better understanding compared to an average market participant.

- Have reliable and applicable data sources that make the moves of other traders more transparent.

- Develop both understanding and ability to interpret those moves with the help of indicators, automatic trading strategy, or a good visualization.

- Continuously evaluate the probability of worst-case scenario taking into account both random and non-random factors.

- Constrain emotions.

- Do not follow illusionary patterns. As humans, we tend to connect the dots even among random data. The reason lies in the cost/benefit comparison: this error is less costly than failing to recognize the real opportunity. Carefully fine-tune your strategy to have a better trade-off between these two errors.

- Have a solid framework which provides necessary and reliable data and allows to execute your decisions instantly.

Q: My commission’s rate is zero. I win or lose 10% with a chance of 50%. Why would I lose in the long term?

Suppose you invest all of your money each time and either gain or lose 10% of it, for instance, by placing stop-loss and take profit orders at the same distance. After winning and losing one time (no matter in which order), your account loses 1% because of 1.1 * 0.9 = 0.99. After winning and losing 50 times each (still, no matter in which order), your fund will shrink to 60% of its original value because 0.99 ^ 50 = 0.6.

This source of losses is especially noticeable for highly leveraged financial instruments such as Futures or FX. For instance, in case of FX with leverage x100, if the asset changes by 0.1%, the account changes by 10% and the example above becomes applicable as-is.

Q: My commission’s rate is zero. The market is random. It goes tick up/down with probability 50%. Why would I lose in the long term?

In such a random walk framework, one may try to set a target with a long or short position and just wait until it is reached. Then repeat it again and again. Will such targets be reached? The answer is yes, given enough time. Theoretically, given an infinite amount of time, any such target will be crossed an endless number of times.

However, when applied to trade, the catch is in requiring the infinite amount of money too. In practice, it means that once you reach zero or get a margin call even earlier, you are out of position. Thus, you will not be there to pick the profit when the price eventually reaches your target.

Q: What about Doubling Down or “Martingale strategy”?

The “theory” behind this idea goes like this: you have a 50% chance of winning or losing. You put 1 unit at stake. If you win, you put 1 unit again. If you lose, you double your stake. As a result, whenever you win, you cover all the previous losses (if any) and also gain 1 unit.

Due to the fact that betting with 50/50 chance eventually must produce a desirable outcome, it appears a no-brainer winning strategy. Here is an example that demonstrates this strategy. We start with an account of 50 units.

| Win=1; Lose=0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Currently at stake | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 1 |

| Account balance | 51 | 52 | 51 | 49 | 45 | 37 | 53 | 54 |

There are 4 wins, and as expected we gained 4 units. This strategy is popular because of the gambler’s fallacy also known as Monte Carlo fallacy. It’s a false belief that nature will “balance” the outcomes according to expected probability and therefore the likelihood of a specific result (e.g., winning) becomes higher when it didn’t occur for a long time.

However, as you can see in this example, if there were one more loss in a row, we would be out of money after just five losses. The deeper your pockets, the longer it takes on average to get out of money, but eventually, it will happen. In real trading there are also other non-random forces can balance or unbalance the outcomes, but they should not be confused with this fallacy.

Q: I cherry-picked the best performing trading strategy out of 1000. Why would it lose in the future?

An important question to ask is: “Why did it perform so well in the past?”. If you don’t have a clear answer, then probably it will lose in future due to phenomena called Regression toward the mean.

Here is an example: imagine there is a large group of N traders. They all trade in real accounts and share their trading actions and results in real-time. You are being offered to pick a winner according to your criteria (e.g., Sharpe Ratio, Maximum drawdown, or Maximum profit, etc.). You also can follow his trading actions manually or even automatically.

This is a model of eToro, for example. Let’s put aside an important slippage factor, consider zero commissions and no other trading costs. Still, if there is no fundamental explanation of why that winner was the winner, then his future performance will most likely become worse.

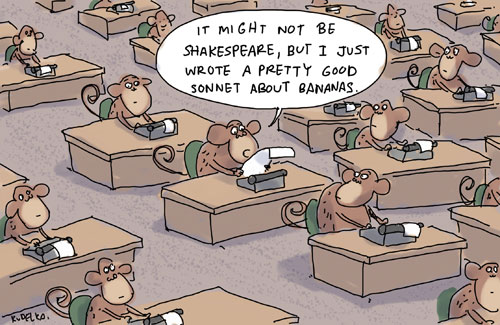

To explain why try and imagine that instead of N human traders there are N monkey traders who got access to trading buttons. Obviously, we do not expect them all to achieve the same performance. Instead, there will be a distribution of monkeys trading results where some of them are negative, but some positive.

Even if we set very harsh criteria for the past results of the winner, given a large enough number of monkeys we will find some who matched that criteria. The more monkeys we have, the better will be the performance of the best of them. But because the particular winner monkey has no outstanding trading skills, it will most likely get worse results in the next trading session.

Same phenomena will occur when instead of following “the best trader” we chose an automatic trading strategy out of a large pool of them. Needless to say that a trading strategy that has too many parameters that were fine-tuned on historical data, suffers from a similar problem.

To summarize, without a reasonable justification of why did a trading strategy performed well in the past, there is no reason to believe that it will perform well in the future.

Q: My trading strategy has fundamental reasons to perform well. Why would it perform worse in the future than now?

The market always tends to equilibrium. Finding a profitable trading strategy means having a high ROI (return on the investment) of the effort to develop, implement, and to run it. Ironically, such a high ROI is also called market inefficiency. But these opportunities attract other investors who increase the competition and make the market more “efficient” reaching the equilibrium.

Here is an example of our R&D playground. We have developed a virtual exchange, and generated hundreds of simple trading agents who can randomly send orders to that exchange, and also to modify or cancel their orders as in real exchange. The longer the trading session was, the wider was the distribution of the profits (P&L) of the agents. As expected, the total sum of their P&L at each moment during the trading session as well as at the end was zero.

Then we created another generator of trading agents. This one aimed to mimic the behaviour of a very primitive Market Making by increasing the chances of sending a Sell order above the current price and a Buy order below it. After mixing the two groups in a single trading session, we found that “market makers” performed significantly better and had positive P&L while almost all agents from the first group had negative P&L. Obviously, a human trader from the first group would decide to switch to the market making strategy in such environment, and at some point, there would be no traders in the first group to take advantage of. Also, because the trading strategy of market makers was so primitive, there is a place for another trading strategy that exploits their weak spots such as price trends and sharp movements. This leads to a conclusion that any significantly profitable trading strategy is a temporary opportunity.

To conclude, when examining a potentially profitable trading strategy we need to be able to answer the following questions: Why and how this strategy will stop being profitable? Will we notice when it happens? If we don’t have answers to these questions, there are probably some unjustified assumptions involved.

Q: Can I reduce the risk by using take profit (TP) and stop-loss (SL) orders?

This helps to limit the maximum loss of each trade, but in the long term, the result depends on your competitive advantage. The price will eventually reach either TP or SL. In a framework of random walk the probability of reaching TP before SL is given by SL/(TP + SL), and the probability of reaching SL before TP is 1 – SL/(TP + SL) = TP/(TP + SL).

For instance, you set TP=20 ticks, and SL=10 ticks. If the price moves randomly, it will reach TP before SL with probability 10/(20 + 10) = ⅓ = 33.3%. For your trading to be profitable in the long term, you must reach TP before SL in more than 33.3% of your trades. In other words, to have better performance than it’s expected from a random decision-maker.

The additional risk of using SL or Stop orders is having those orders triggered just before the price moves in the desired direction and reaches TP when you are out of position. Most traders have such unpleasant experience, and it is frequently referred to “bad luck” which is partly true, but sometimes this is caused by large traders who have a good estimation of where concentrations of Stop orders are. This gives them an opportunity to trigger those orders and trade against them.

Also, for SL to be triggered, it requires just a single trade to occur there. But when trades start happening at TP it will not necessarily execute your TP order. This is why large traders put orders in advance to get a better place or higher priority in the orders queue.

What is the ultimate piece of advice in regards to risk management?

Having a robust trading strategy provides a clear set of possible actions, allowing traders to be more prepared to deal with all sorts of unfortunate circumstances. But regardless of how you choose to handle risks, you must continuously revise and adapt your risk management strategies.

EXPLORE MORE USEFUL CONTENT ↓